The Renaissance, spanning from the 14th to the 17th centuries, marked a transformative period in Western culture. Intellectuals, inspired by the accomplishments of ancient societies, shifted their focus from religious tenets to humanism, affecting art, literature, architecture, and politics.

Artistic Recognition Before the Renaissance

Before the Renaissance, the idea of an ‘Artist’ as we know it today did not exist. Craftspeople worked in guilds or workshops. There was a master who taught skills to apprentices through structured learning and a passing down of skills. Visual artists of the time graduated through the development of skills and traceable accomplishments. At that time, it was patrons who funded the work of these workshops who would have received recognition rather than the artists themselves.

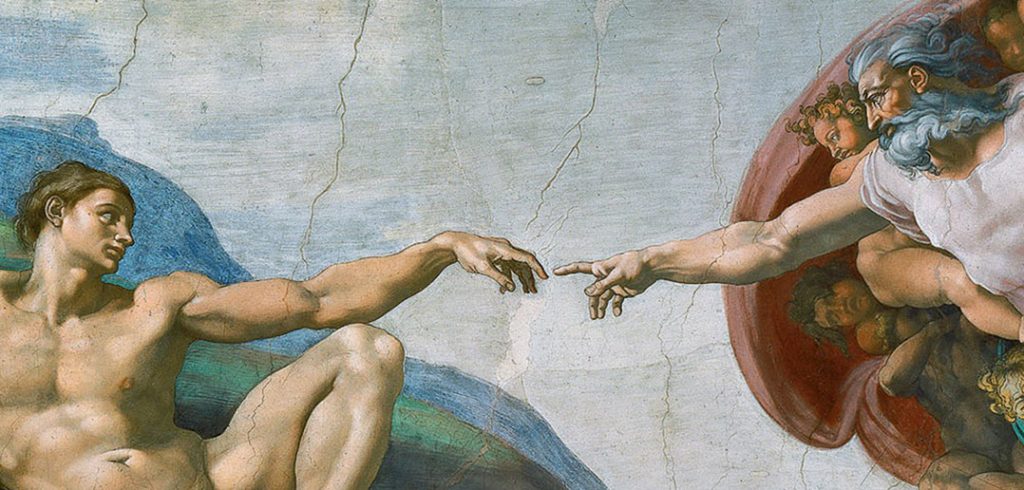

The Renaissance era emphasized humanism, prioritizing the individual over religious viewpoints. This led intellectuals to champion individual artistic genius, considering works produced collectively or traditionally to be inferior. During this time, painters convinced their patrons to pay them based on the merit of their works rather than on square footage which had been common until this time (Morelli, 2023).

The Renaissance’s Influence on Artistic Recognition

This period also drew a line between craft and fine arts, emphasizing that true art originated from an individual artist’s unique voice, while guild workers were categorized as skilled technicians.

A book profiling the lives and biographies of artists, “Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptures and Architects” by Giorgi Vasari during this era, launched artists into celebrity status. Suddenly, painting, sculpting and architecture were considered art forms; everything else was relegated to the inferior place of artisan. It’s important to note that this is a culturally Western ideology. Other cultures often consider the traditional crafts of their cultures as among the most lauded art forms, such as totem poles in indigenous culture. Even today, we require an artist to show innovation to be considered significant. For centuries and even today, in many cultures, the display of expertise or a skill can be respected as art.

Feminine Ideology During the Renaissance

As men increasingly explored their own identities in the humanistic framework, women’s lived experiences remained largely unchanged compared to the Middle Ages. Women were discouraged from participating in activities considered masculine and were instead pushed towards domestic roles. These roles usually involved domestic tasks, and they were chosen for women based on three main conditions (Henry, 2021)

- The tasks were monotonous and repetitive, making it easier for women to also focus on childcare.

- These tasks could be paused and resumed—again, so women could attend to kids.

- They were safe jobs, meaning there was no risk of kids getting hurt—so no heavy machinery involved.

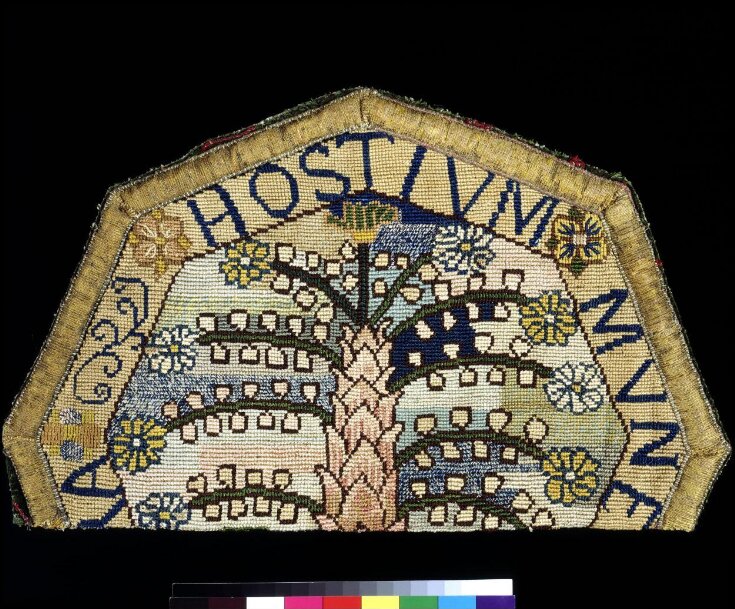

For well-off families, sewing wasn’t even done at home; it was considered a job for professionals. This included the art of embroidery, which was done in specialized guild workshops. But as the Renaissance economy boomed, generational wealth became a big deal as did the ideas of status and reputation. This ended up pushing most women even deeper into roles that emphasized purity before marriage and fertility afterwards (Iacob, 2023). Basically, a woman’s behavior was a direct reflection of her family’s reputation. During this time, the difference between genders was a huge topic of conversation amoungst intellectuals. There were varying opinions on the acceptability of educating women, as it was seen as a threat to male supremacy, this led to an emphasis on needlework as a major component of girls’ education to deem it appropriate for the weaker sex.

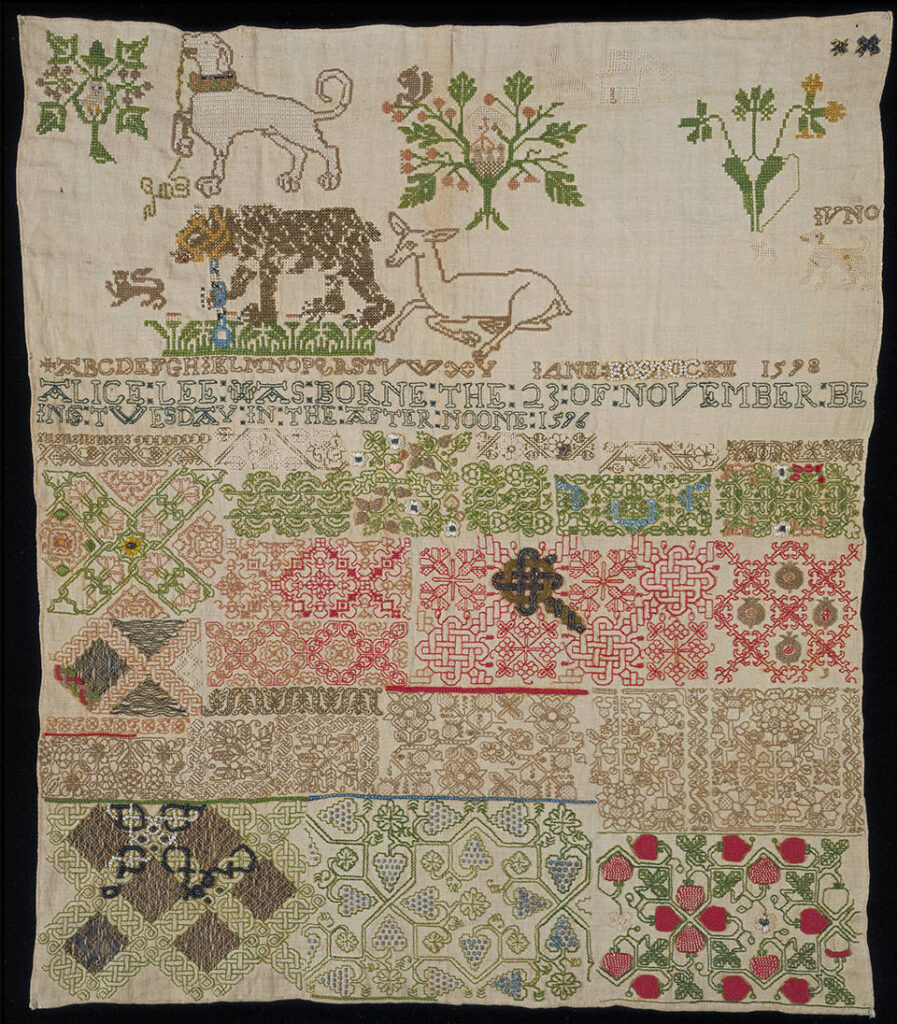

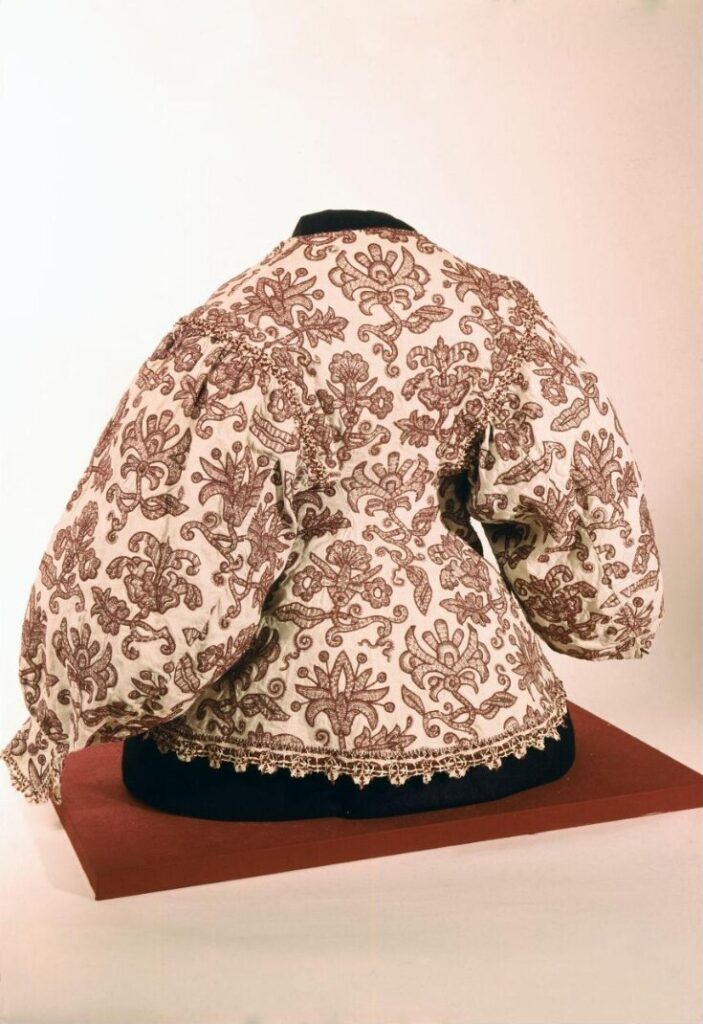

During this time, embroidery started to play a unique role. It became the yardstick by which a woman’s education, social standing, and even her femininity were measured (Parker, 1991). The growing middle class, wanting to mimic the lifestyle of the nobility, sought wives who were educated in “leisurely” arts like embroidery. If a woman had the time for such crafts, it signaled that her husband was wealthy enough that she didn’t need to work. Embroidery itself was a luxury; the more you could afford to have on your curtains, bed hangings, and furniture, the wealthier you appeared.

Women used to have a big role in embroidery guilds during the Middle Ages. But societal shifts, like wars and plagues, pushed them out. Many took up freelance embroidery or left the field altogether. Freelance work done by women was often undervalued compared to that of guild workers. And as guilds began closing down due to decreased demand, embroidery became a domestic task. While girls and women were still expected to embroider, it was no longer a money-making skill but rather an indicator of chastity and wealth.

Depictions of Women in Renaissance Embroidery

As women became more confined to the home, so too did their depiction as subjects of art. The Virgin Mary who had previously been depicted as queenly and fertile in giving birth and midwifing for her cousin Elizabeth begins to be portrayed differently. We see her become secondary to the Baby Jesus in depictions or purely maternal. She is portrayed breastfeeding, and scenes of birthing and midwifery disappear. St Margaret, who in the Middle Ages was depicted as a fierce dragon slayer of a woman, transforms into a meek and helpless young girl, who is martyrd for her chastity (Parker, 1991).

The Renaissance, with all its advancements and changes, did little for women’s rights or appreciation for embroidery. While society was pushing men to explore humanism and individual genius, it was pushing women right back into the domestic sphere. Embroidery, which once had professional merit and was done in guilds, became a domesticated craft aimed at signaling a woman’s “proper” upbringing and her family’s status. While men were praised for their artistic and intellectual contributions, women were relegated to roles that emphasized chastity, purity, and home-making. Embroidery, once a respected art form, became another way to keep women at home.

I have found this a challenging learning experience in that as a creative person, I view myself as a practitioner rather than an artist. I believe that time spent and work done creates better art than pure talent. Perhaps this is why I find myself drawn to the labour that is embroidery even though I’m not always aesthetically pulled to it.

Other Posts in this Series:

Changing Persepectives on Embroidered Art and Feminine Identity

Opus Anglicanum: The Golden Age of Embroidery and its Feminine Narrative

Sources:

Embroidery – a history of needlework samplers · V&A. (n.d.). Victoria and Albert Museum. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/embroidery-a-history-of-needlework-samplers

Gosier, C. (2016, September 8). In Scholar’s Work on Michelangelo, Insight into the Renaissance Mind. Fordham Newsroom. https://news.fordham.edu/inside-fordham/in-scholars-work-on-michelangelo-insight-into-the-renaissance-mind/

Henry, R. (2021, January). Stitching Women: A short history of embroidery and what it means in the novels of Jane Austen » JASNA. https://jasna.org/publications-2/persuasions-online/vol-42-no-1/henry/

Iacob, A. (2023). The role of women during the Italian Renaissance. TheCollector. https://www.thecollector.com/role-of-women-in-italian-renaissance/

Morelli, L. (2023, May 3). What’s the difference between art and craft? Laura Morelli: Art History, Art Historical Fiction, Authentic Travel. https://lauramorelli.com/whats-the-difference-between-art-craft/

Museum, V. a. A. (n.d.-a). Panel | 1570-1585 | Mary Queen of Scots | V&A Explore The Collections. Victoria and Albert Museum: Explore the Collections. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O138485/panel-mary-queen-of/

Museum, V. a. A. (n.d.-b). Waistcoat | c.1640 | V&A Explore The Collections. Victoria and Albert Museum: Explore the Collections. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O115768/waistcoat-unknown/

Parker, R. (1991). The Subversive stitch: embroidery and the making of the feminine. Womans Art Journal, 12(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.2307/1358191